The Pathos of the Patron: Peggy Guggenheim and the Art of Estrangement

A fracture between wealth and belonging, and the mirror she found in modernism.

✧ Editors Note: This series will be free to read until September 30, 2025, when the series becomes exclusive to paid subscribers. Thank you for being here at the beginning. ✧

“I am not an art collector. I am a museum.”

Peggy Guggenheim

Peggy Guggenheim is one of the most significant figures in the history of modern art.

Her discerning eye built a canon of taste that was both cultivated and compulsive. She was not a woman of grace, but of appetite. She consumed whole, and spat out bones with no remorse. Her life was punctuated by despair, possession, and sudden loss, yet what she made from it was singular: a world powered not by lineage, but by longing.

She has always fascinated me; I picture her in seafoam green, drifting through the canals of Venice, her thick lashes behind those round surrealist glasses. She wore flowing Fortuny gowns, loud prints, and enormous earrings that clashed in ways only she could command.

She rejected the title of artist, but became the modern version of a patron. She was eccentric, essential, and often misunderstood. She was a museum of other people’s madness and devotion, a temple filled with borrowed visions in which, I believe, she saw glimmers of herself.

In this edition of Personas, we examine the myth of Peggy Guggenheim through Ethos, Pathos, and Logos—and discover how her style reveals the cost of seeing without being seen.

Section I: Ethos, The Mask of Character

Ethos /ˈē-ˌthäs/: From the Greek êthos, meaning character, custom, or moral nature.

If there was one word I had to choose to define Peggy Guggenheim, it would be bold. Everything about her life, the way she moved, collected, spoke, and dressed, was bold, often bordering on brazen. She had a lust for more: for knowledge, for intensity, for disruption. It oozed, like turpentine bleeding through oil.

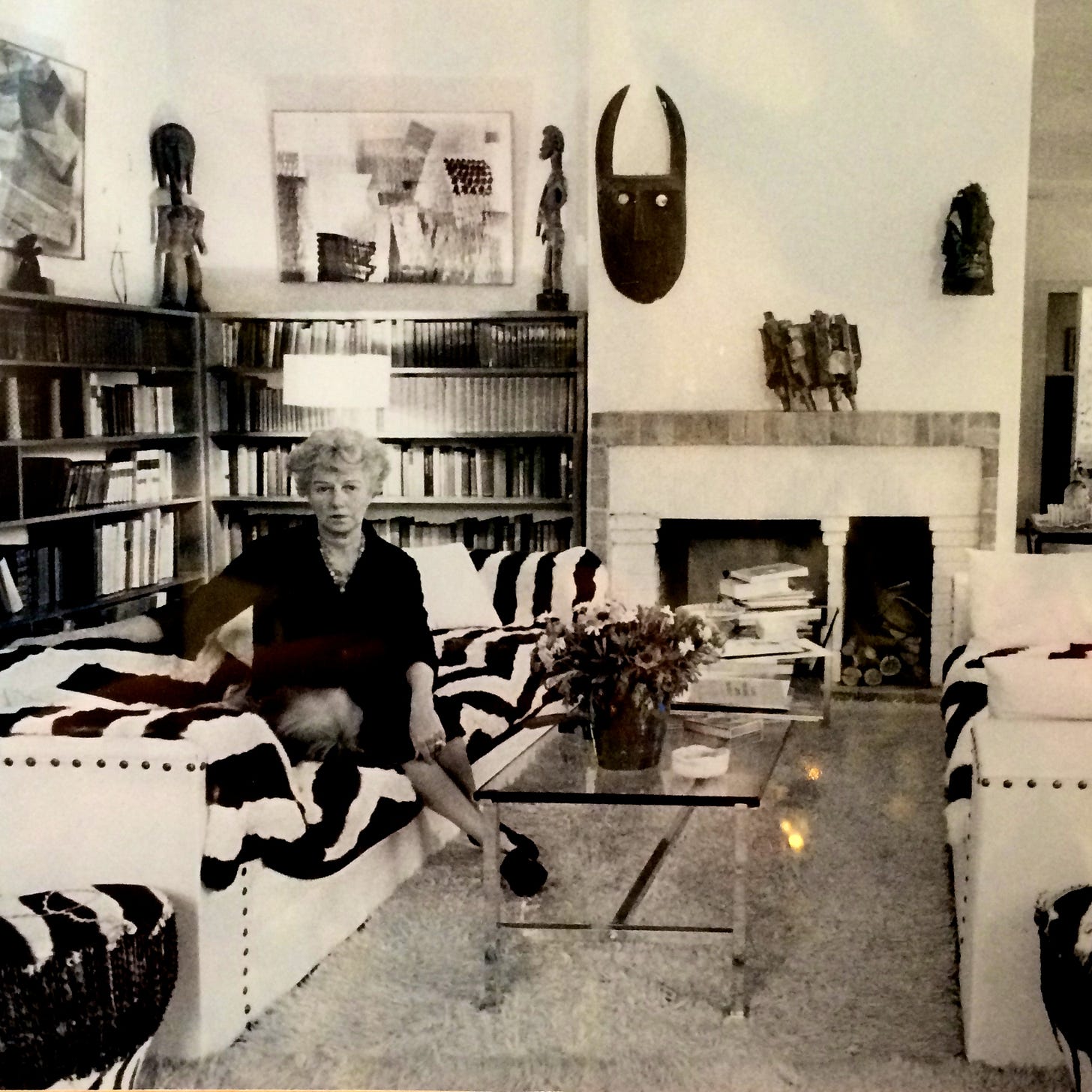

From Paris to London, and eventually Venice, Guggenheim created spaces where painters, writers, and thinkers could collide. She dressed as deliberately as she collected: long Fortuny gowns, caftans in violent prints; each piece of jewelry was less an accessory than an assertion. Denied entry into the world of her birthright, she fashioned a new one entirely her own.

Her personality was equally commanding. She was demanding, often cutthroat, and rarely paused to consider how her words might land. As a patron, she provided critical support to artists who would go on to define their era, including Jackson Pollock; once referring to him as her “spiritual son.” But like many of her relationships, theirs was fraught. Some artists resented her influence, felt suffocated by her involvement, even as they depended on it. She had strong opinions and rarely held them back. Peggy didn’t just support the work, she shaped its context. She was never passive. That wasn’t in her nature.

And yet, what stays with me most is her self-description: “the poor Guggenheim.” On its surface, it was about money, she received a notably smaller inheritance than others in her family. But I don’t think she was speaking about finances. I think she meant that she felt poor in spirit. Her life, to me, reads as a long, relentless search for something missing; a hunger for a feeling she may not have recognized, even if she had ever found it.

Guggenheim did not consider herself an artist, but she took pride in her ability to recognize artistic genius early. She once vowed to “buy a picture a day” at the height of her collecting. Her acquisitions were impulsive, sometimes erratic, yet always strategic. She was neither the creator nor the muse, I suppose she was, in reality, the catalyst. The witness of a new age.

Section II: Pathos, The Wound of Emotion

Pathos /ˈpā-ˌthäs/ (noun) From the Greek páthos, meaning suffering, experience, or emotion, the emotional resonance of one’s feelings.

At just 13 years old, Peggy Guggenheim lost her father when he died aboard the Titanic in 1912. This loss left a massive scar upon her life and psyche, and continued to follow her throughout her life. Upon his passing, it was revealed that she received a much smaller inheritance than many of her relatives, even including her cousins and other members of distant family. In her memoirs, she later wrote about feeling excluded from the family’s inner circles, she had been cast out for the simple fact of being. Orphaned, every way but legally.

It makes sense, then, that she would develop a kind of wanderlust. She lived in multiple cities throughout her life, Paris, London, New York, Venice, often surrounding herself with avant-garde artists and intellectuals. Part of it was aesthetic, but part of it was emotional: a desire to find home, to belong. She longed to be part of something larger than herself, and her life’s work of cultivation answered that ache. The way she dressed was ornamental, eclectic, layered like a silk cocoon. Mismatched shoes, and kohl-rimmed eyes; flowing caftans in bold prints, heavy earrings that brushed her shoulders, turbans twisted high above her brow.

Though she thrived in her chosen cultural circles, her romantic life was far less forgiving. Guggenheim had numerous romantic and sexual relationships, including two marriages and affairs with several artists. These trysts were intense but short-lived, and she often spoke openly, candidly, about her difficulties with intimacy and emotional attachment. During World War II, she used her growing wealth and influence to help artists, including Max Ernst, whom she later married, escape internment and flee Nazi-occupied Europe. Being half-Jewish herself, and often made to feel like an outsider because of it, she knew what it meant to live at the margins, even among the elite.

Most tragically—and most devastatingly—her deepest wound was made public when her only daughter, Pegeen Vail Guggenheim, died by suicide in 1967, at the age of 41. It is a cruel symmetry: a woman who lived in a vacuum of emotional withholding, unintentionally or not, created the same environment for her children. It was known that their relationship was strained; While Peggy poured her energy and time into artists with no name recognition, she offered little support to her daughter, an artist in her own right. She publically spoke down about her daughters art, and minimized Pegeen’s mental and emotional struggles. Perhaps they mirrored something too familiar.

Maybe that’s why she couldn’t help. Maybe that’s why she didn’t. Maybe, in the end, it was easier to nurture the genius of strangers than to face the fracture in her own bloodline. Peggy Guggenheim could see the future in art, visions splashed on canvas, but in her daughter, and perhaps in herself, there was only a void.

Section III: Logos — The Mirror of Thought

Logos /ˈlō-ˌgäs/ (noun) From the Greek lógos, meaning word, reason, or discourse. The logical structure behind an idea.

It was not creation that made Peggy Guggenheim an artist, but her ability to cultivate. She collected art, not as a muse or a subject, but as someone who recognized its value before the world did. She catapulted the lives of many artists simply by including them in her collection and exhibitions, and she was unapologetically specific about what she liked.

She was drawn to surrealism, abstract expressionism, and other radical movements that defied conventional form. These choices reflected her interest in the unconscious, the irrational, the emotionally raw. She seemed to see bits and pieces of herself in the works she loved. She spoke of them with real passion, not with the prose of a theorist or historian, but as someone who felt deeply. The art she collcted moved herl; I believe she adored what she adored because, on some unspoken level, she thought it might recognized her back, almost like a friend.

The emotional resonance she found in the work of others must have been both a thrill and a kind of despair, to feel as though you could only see yourself reflected back in the works of others, in someone else’s vision. Despite creating one of the most significant private collections of the 20th century and opening it to the public, Guggenheim often expressed feelings of exclusion and dissatisfaction. Though she became a central figure in the history of modern art, she remained, by her own account, emotionally and socially isolated.

It’s painful, almost haunting for me, to know that the woman who quite literally reshaped the cultural world could feel so utterly alone. She took her family’s legacy, once built on mining and metallurgy, and turned it into something strange and luminous, something made of vision instead of ore. And yet, even in her most enduring work, she felt alone. I suppose I should say that she was alone, because if you are surrounded by people and still feel unseen, it might almost be kinder to be forgotten.

Closing Reflection

“I dedicated myself to my collection. I made it my life’s work. I am not an art collector. I am a museum.”

I think Peggy spent her life trying to define who she was, outside the standards she was born into; standards that were always too narrow, too indifferent, too inherited. She blurred the line between adoration and control. What she loved, she needed to possess. What she possessed, she often misunderstood. Her longing, to find herself, to matter, to be mirrored, became the foundation of everything she ever collected.

Peggy Guggenheim was buried alongside her beloved dogs, in the garden of her home in Venice. Her family lies elsewhere, scattered across mausoleums and cemeteries, her daughter laid to rest 700 miles away. Even in death, Peggy Guggenheim remained apart, destined only to reside in her own world. Hers was a hunger no inheritance could feed. A woman of appetite. A woman of absence.

There is more I could say. But perhaps this is where it ends.

For her, maybe, it was enough.

With great personal aesthetic,

Alexandra Diana, The A List