“Elegance is elimination.”

Cristóbal Balenciaga

Old Money: Luxury as a hereditary condition.

The core stylistic elements of Old Money are Discretion, Polish , Chromatic Discipline, Familial Silhouettes and the Patina of Time

Where Preppy codified belonging, Old Money perfects restraint.

Before logos, there was tailoring; before influence, there was inheritance.

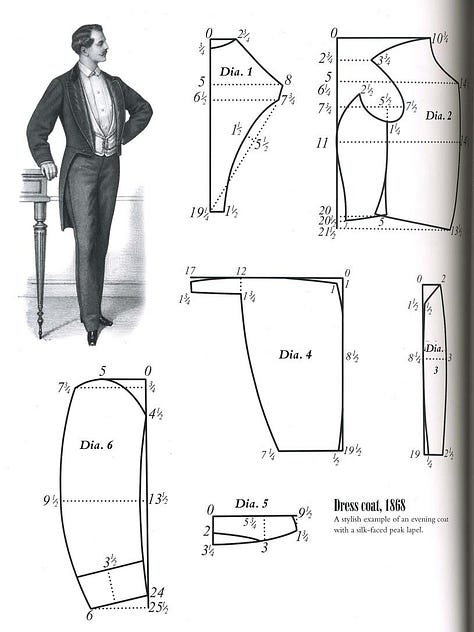

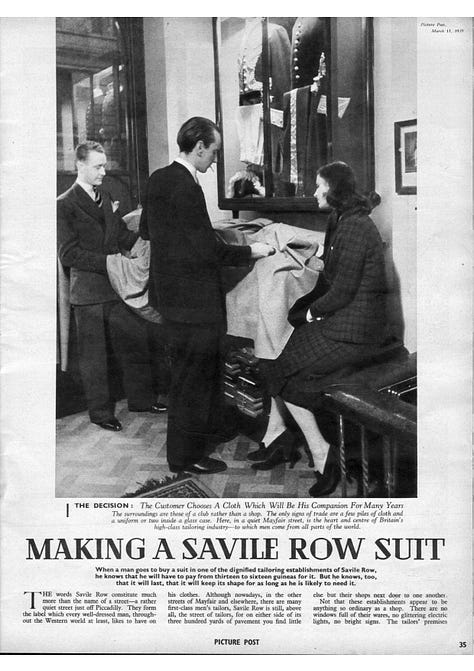

Far from couture houses, nestled in the country side, among Britain’s landed elite of the 18th and 19th centuries, clothing served function first. From riding habits, fox-hunting tweeds, waxed jackets, and Savile Row tailoring, clothing was an investment, and was referred to in the same way one would speak of their estate, well-kept. For generations, tailors worked from family patterns passed down to create garments for whole lineages, literally creating templates of continuity. Old Money cannot be described as mere fashion, but in the maintenance of legacy.

After the First World War, ostentation became distasteful as across Europe, inherited families faced shrinking fortunes and shifting class structures. The British upper class, once defined by indulgence, rebranding simplicity as an act of virtue, and “good taste” emerged as the new moral currency.

In the 1920’s, The press coined the term Serviceable Chic to praise women who wore the same tailored suit all day long, from luncheons to funerals, even countryside walks. The quiet repetition of garments became an emblem of moral steadiness. Luxury could now be defined through your character.

As wealth crossed the Atlantic, it was adopted by America’s first industrial dynasties: the Astors, Vanderbilts, and Rockefellers.

Wanting to feel the way they imagined the British felt, the American elite commissioned tailors from Savile Row to travel across the ocean to create their new wardrobes: structured suits, restrained palettes, wool and tweed softer than memory. In the drawing rooms of Newport and the estates of Long Island, luxury became architectural, paneled wood, muted lighting, everything designed to appear inherited. When the Rockefellers commissioned their tailors, they requested muted linings in jackets and coats, so when hung open, the jackets would look discreet against the interiors of their homes. This became the Americanization of heritage: the belief that power should always look contained.

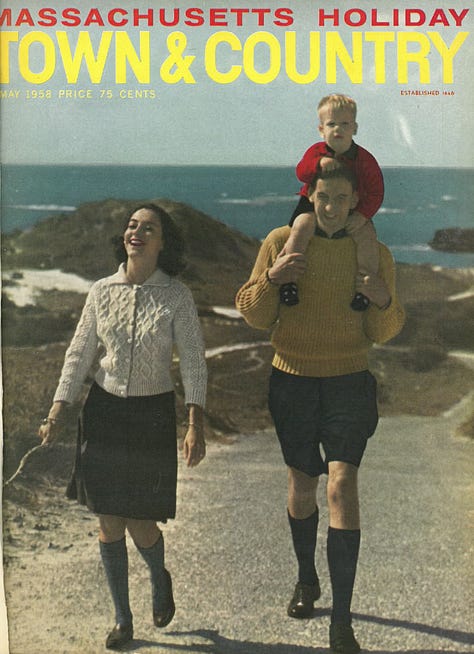

By the 1950s, this performance had perfected itself. The American upper class translated their austerity into ease. Magazines like Town & Country and House & Garden made restraint fashionable, selling an aesthetic of moderation to those still building their fortunes.

But beneath the beige cashmere and clean tailoring was a distinctly American contradiction. What began in Europe as genuine inheritance became, in America, a replica. The irony of now achieving great wealth was that it’s greatest display was the ability to appear indifferent to it.

The American Evolution of Old Money

The 1940s saw restraint, elevated. Wartime rationing demanded precision, hemlines shortened, palettes muted, silhouettes simplified. Designers like Norman Norell and Claire McCardell made something beautiful out of this seeming nothing: tailored suits, self-belting dresses, and wool crepe that are coveted to this day.

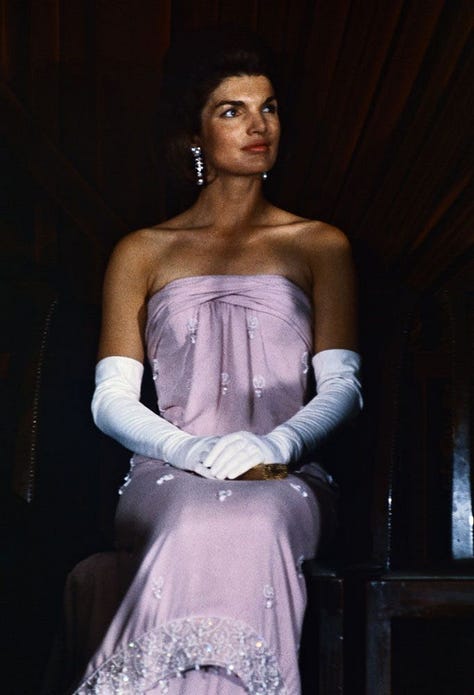

By the 1960s, restraint had turned into a form of aspiration. Cristóbal Balenciaga’s architectural tailoring and his pupil Givenchy’s structured minimalism on Audrey Hepburn made discretion cinematic, something on the silver screen that made it feel marvelous. “The first fitting at Balenciaga is as good as the third elsewhere,” said the great Marlene Dietrich.” In America, Jackie Kennedy was the symbol of new aspiration, and while she didnt invent understatement, but she made it look so natural. All of the sudden, control became glamorous.

The 1970s saw Ralph Lauren translate Old World discretion into New World mythology. What he advertised wasn’t about clothes, it was about belonging. Families in navy blazers, plaid skirts, and knits, posing against libraries, sailboats, leisurly laying in the grass of Spring. He created the visual interpretation of this inherited taste by transforming private moments into a lifestyle that proved you don’t need glitter or gold to be the envy of everyone around you.

By the 1990s, the privacy of Old Money had shed its preppy polish and became something unexpected: sensual. Calvin Klein, Helmut Lang, and Jil Sander reduced fashion to line and texture: silk slip dresses, gray cashmere, white cotton tanks. This level of simplicity was eroticism as America had never seen before: The less you revealed, the more expensive you looked.

Phoebe Philo’s Céline once again redefined modern discretion, her runways etched in fashions collective memory with pristine tailoring, architectural volume, and knitwear that still has us in a trance. Under Philo, restraint became not nostalgic but forward-thinking: a quiet revolution against the performative churn of trend.

Finally, The Row, the brainchild of Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen, has completed the cycle. Their aesthetic feels almost ecclesiastical: Silhouettes cleansed of the mere idea of excess, color drained, minimalism that nears preformance-level polish. Their clothes evoke inheritance without ancestry; they are heirlooms for those self-made enough to afford them.

It’s important to understand that modern interpretations of Quiet Luxury are not acts of inheritance but of imitation. The irony is that what began as a rejection of spectacle has become one of its most marketable illusions.

THE MOST ICONIC EMBODIMENT OF QUIET LUXURY IS BABE PALEY.

Before she became the reigning socialite of mid-century Manhattan, Babe Paley was a fashion editor at Vogue in the 1930s and ’40s. Her aesthetic defined the American expression of discretion: perfectly tailored suits, neutral palettes, pearls and gloves. She famously tied her Hermès scarf around her handbag, an accident that became a trend, though she never commented on it. Truman Capote called her “perfection itself”. What made Paley remarkable wasn’t wealth, but control. She understood visibility as a privilege to be managed. Her clothes were rarely new, just impeccably maintained. Every gesture was edited. She was photographed constantly yet never seemed posed.

THE BEST FICTIONAL EMBODIMENT OF QUIET LUXURY IS CLAIRE UNDERWOOD.

Claire Underwood is the fictional blueprint of composure (speaking directly to Season 1). Her presence in House of Cards redefined what modern power dressing could look like when stripped of performance. Claire belongs to the class of individuals whose refinement feels inherited, not learned; her wealth is social fluency, not capital. Educated, restrained, and impossibly precise, she embodies the psychological perfection of Quiet Luxury: control mistaken for calm. Her wardrobe, sheath dresses, silk blouses, sharply tailored coats, never changes because it doesn’t need to. She represents the Americanization of old-world composure, discipline reframed as elegance,

IN SUMMARY, LET’S REVIEW THE CORE COMPETENCIES OF OLD MONEY ONCE MORE:

1. Discretion

The governing principle of inherited taste. In Quiet Luxury, nothing needs to shout as it is already perfect, perfectly tailored. The cashmere is double-faced, the jewelry inherited, the labels invisible. True luxury conceals itself, and has no need for external applause.

2. Polish

A perfectly steamed silk blouse, a shoe buffed to reflection, tailoring that sits so well it makes even structured pieces look easy. Polish isn’t perfection; it’s the habit of grace. This kind of attention is effortless because it’s second nature.

3. Chromatic Discipline

Color palettes are measured, minimal, and consistent. Ivory, navy, camel, gray: shades that neither age nor announce. These shades move through seasons unchanged, creating the visual equivalent of good posture. Interestingly, its the lack of change that showcases the level of luxury that feels unobtainable.

4. Familial Silhouettes

Quiet Luxury favors shapes that have already proven themselves: the straight trouser, the clean sheath dress, the box-cut blazer. These are clothes that reappear across decades because they work. A wardrobe built on proportion, not reinvention.

5. The Patina of Time

Proof that beauty matures. Leather darkened by use, wool softened by wear, pearls warmed by the skin, a gold bracelet that once belonged to someone else. Age becomes the finishing touch money cannot buy. The Patina of Time turns ownership into stewardship, with the understanding that care itself is the final layer of polish.

Old Money is often discussed as if it were a trend, but trends depend on visibility, and this aesthetic was built to resist it.

What people now call “quiet” was never new; it simply feels that way in contrast to all the noise. It belongs to those who dress for continuity, not attention—who understand that the most sophisticated form of self-expression is repetition. [link]

To live inside this aesthetic is to reject fashion’s churn, as Quiet Luxury endures not because it reinvents, but because it remembers.

“What is left unsaid defines the rest.”

Virginia Woolf

With great personal aesthetic,

Alexandra Diana, The A List

Aesthetic Activation: Old Money

Choose one item you wear often and one you’ve kept only for show. Keep the first. Donate the second. Quiet Luxury begins where performance ends.